Introduction

Software development has always been about one thing. Shipping new features and delivering to consumers as fast as possible. The story doesn’t change, in fact, it only gets more severe as technology advances. The density of software in the market leaves no room for stale applications, buggy features, or unreliable services. Business outcomes are almost directly tied to IT performance. In addition, many applications are under heavy stress from activity all over the globe, all day, every day. We require high security standards to protect our customers from potential cyber threats, and to protect our investments on-prem and in the cloud. And we’re asked to continue improving the quality and reliability of our existing software while delivering new features to delight the user. Despite commitments to Agile software delivery, most teams face a bottleneck often ignored unless called out directly. It takes too long for your code to go from your editor; to production. And it’s probably not because you’re slow at writing code. You could be, I don’t know. I’m not particularly fast myself. There are steps in the process of pushing code that simply take too long. The good news is they can be either removed or modified to make you and your teams more efficient.

Trunk based development is a concept that I learned about through my own experience in product development. Trends come and go in software, and buzzwords start to introduce a foggy layer of abstraction over the actual implementation and benefits that can be reaped from the individual concepts. For instance, DevOps, Agile, CI/CD, and micro-services now flood the industry. They all have a singular definition, yet there are so many intricate details and variations that are discussed less frequently. My goal is to introduce trunk based development from several angles to make it more approachable for teams who would like to experiment. I want to bring it down from “pie in the sky” to an attainable goal you can take back to work with you.

Git Flow / Traditional Software Development

A common approach to change management in software is for developers to branch off of either a mainline or development branch of the repository. They create feature branches to preserve the integrity of the main branch while they write changes intended to be merged back into the main branch downstream. When changes are complete, a pull request is opened and the code goes through a technical review by at least one peer, or in some cases a governing body of reviewers. Reviewers can request the author to make changes to the feature branch to meet standards and correct potential issues before they will approve the merge. A discussion is usually formed within the PR and the author will push new changes to the feature branch to satisfy the reviewers. When the branch meets the standards of the reviewers, and the required number of approvals has been reached, the PR is merged into the mainline branch and the work can be sent to the next stage of its lifecycle. This is usually a working or staging environment that allows functional testing, visual design review, and possibly performance testing to be performed on the new feature. Once the feature has passed the standards to be put into the production environment, a release is scheduled and eventually deployed to production.

This model is widely adopted and is considered a successful approach to working in version control with teams. It suits contributors of open-source software on Github because contributors are usually not working on the project full time and may need a long-running branch to complete a task or issue over weeks or months. Git flow allows plenty of visibility and control over the main branch and prevents unwanted changes from being released to the production environment. In this model, releases are often thoroughly tested and vetted in lower environments before going to production. The cadence of releasing software tends to be on a monthly or quarterly basis. Although, it’s not uncommon to have high-performing teams working in this model doing weekly releases.

What is Trunk-based Development?

A one line summary from trunkbaseddevlopment.com

trunk-based development is a “source-control branching model, where developers collaborate on code in a single branch called

trunk, resisting any pressure to create other long-lived development branches by employing documented techniques. They therefore avoid merge pain, do not break the build, and live happily ever after” (1).

Now that we’ve discussed Git-Flow, how is TBD different? Git flow is highly dependent on branches, which can cause problems. Teams working in branches can become disconnected. Lack of communication can cause unexpected merge conflicts, regressions due to a bad merge, and worst of all: duplicated code. Trunk-based teams are committing early and often to the main branch, which allows contributors to share work as they build.

In many cases, trunk is linked directly to the production application. This means the build cannot be broken, and the team’s priority is to maintain releasability. This often requires a mindset change. It’s difficult at first to grasp the concept of having work-in-progress committed to the trunk and ready to be released at any time. In most cases, using feature flags to corral changes to existing code is an excellent way to manage this paradigm. By consistently maintaining a releasable main branch, you eliminate the need for a “code freeze” to stabilize the environment in preparation for a release. The book Accelerate, which documents the process of gathering data for the 2017 state of devops report, claimed “developing off trunk/master rather than on long-lived feature branches was correlated with higher delivery performance” (2). Performance in this context is measured in terms of release frequency, or lead-time. Since the core concept of TBD is maintaining releasability, product teams can release to production on a more frequent basis. In advanced cases, multiple times per day. In other words, changing your branching model can completely the way you and your team work for the better. However, simply naming your branch trunk and merging long running branches back to trunk often is’t quite enough to get you to the goal.

Example No. 1: The Vicious Cycle

Consider this scenario: Jack is an engineer developing a large feature for the application. At the beginning of the two-week sprint, he branches off the main branch and begins work. After a week, he opens a PR with his changes. It’s a large diff and will take his teammates a significant chunk of time to review it. The team requires two peer approvals before the feature branch can be merged into the development branch, and everyone is working on features. After sitting un-reviewed for about a day, his teammates set aside enough time to review the PR. One teammate approves, and another leaves requested changes and a promise to approve after Jack has completed the tasks. Another day passes and Jack completes all of the requested changes; his teammate approves. The PR is merged into the main branch and deploys the application to a staging environment. The QA team and Design team are notified the feature is ready for testing. Jack takes a new story and begins work on a new branch. That day, the QA Team comes back to him with issues that came up during testing. In addition, the design team has tweaks to the interface that need to be made. There are now only a few days left in the sprint, and Jack opens another branch to fix the bugs. He opens another PR and requests a review from his teammates, which is quickly reviewed and merged. Jack notifies the team that the feature is ready to be re-tested and gets back to work on the other user story. Miraculously, the first story passes both QA and design and is sent to the product owner for final verification before the end of the sprint.

This experience may sound familiar. It does to me.

Let’s examine. What are some of the issues that affected Jack’s performance during the sprint?

- He didn’t ask for any input during the development phase which resulted in a long code review process.

- He wasn’t able to get feedback from QA or Design until after all of the work his interpretation of the feature was completed.

- In the time the PR was sitting, it was getting stale. Increasing the chance for merge conflicts.

This scenario highlights a few issues that can be alleviated through the implementation of TBD as well as general agile concepts.

Huge PRs are a well-known nightmare for software engineers. The memory of a friendly note from a colleague asking for a “quick PR” on a 150-file diff on Friday afternoon is enough to send shivers down my spine. It also forces the reviewers to choose between a quality review and meeting their own deadlines. Delivering code in smaller, digestible chunks leads to faster feedback loops with peers, faster deployments and ultimately reduced lead time. At scale, trunk-based development is aligned with the theory of having short-lived feature branches (think hours, not days) that are branched off of trunk, and merged back in. This requires a shift in the planning phase of the work, to ensure it is broken down into the smallest vertical slices possible, and engineers can deliver increments in less than a day.

It’s likely that Jack’s feature branch was in a semi-broken or a state otherwise not ready for production until he was ready to merge. In order to become releasable, Jack would need to shift his approach from “building a feature” to “releasing the first deliverable increment”. If Jack had been able to release within hours of starting his task, he could have asked for initial feedback from not only his fellow engineers but from QA and Design before he gets too far down the road. When you shorten the feedback loop, rework becomes smaller, or in some cases non-existent. It sort of dissolves into the development workflow and isn’t such a switch in context.

Example No. 2: Adopting TBD

Let’s consider a product development team that is not using TBD. The team uses four branches, development, working, staging, and production. They work off of the development branch, and the other three are configured to deploy automatically to the respective integrated environments when changes were merged. On commit, Jenkins triggers an automated build to deploy code to the respective environment. Engineers will create feature branches and merge via a PR to development, where a CI process runs unit and integration tests. Once that passes, the engineer can merge development into working to trigger the deployment to the integrated test environment. The team is working in two-week sprints and deploys to staging after every sprint. The stakeholders run smoke tests and sign off on the production release shortly after. If an issue occurs in an elevated environment, a PR is created against the branch and subsequently merged down to development.

This is a relatively strict workflow for the team. They have a structured process of promotion and the engineers don’t have full control over the release process. Like Jack’s team, this creates long lead times between development and production. So, how does trunk-based development help this team? And what does the implementation look like from a CI and release process? This team deviates from TBD in several ways:

- There are too many branches to maintain. Engineers have to consciously maintain the state of their work in each environment.

- Allowing changes to the release branches can cause merge conflicts and pain. It can also introduce regressions to other environments.

- The

working,stagingandproductionbranches are kept alive for a series of releases. In a branch-for-release strategy, “the principal mechanism to land code on that branch is the branch creation itself” (3).

Since the team has three integrated environments, we’ll consider working to be our new trunk, since it continuously deploys to the working environment. development, staging, and production will be deleted. The team now works off of main, formerly working. The release process to staging and production is now broken, and the CI job has been abandoned. To re-institute the “Don’t break the build”, we’ll add a pull-request trigger to the main branch. The CI build will run whenever a pull request is opened for main, and a branch policy will require the build to pass before merging. Now commits are flowing to the main branch, and we need to handle a release. Staging and Production will both release the same way, but instead of deploying code from a branch, they will deploy from a git tag. When the team is ready to release, they can tag the commit in main and trigger the deployment with the specified tag, say 1.21.0. When the release is verified and ready to be deployed to production, the same tag can be deployed to prod.

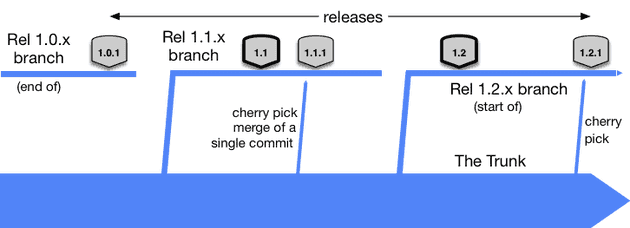

In this model, we have controlled releases to production. The working environment is our proving ground and is constantly updated. If an issue is found in the production environment on version 1.21.0, a release branch can be created from that tag, a fix applied, and then re-tagged as a patch. We’ll call it 1.21.1. However, to prevent the chance of forgetting to merge that fix down from the release branch to the trunk, fixes should be made on main, tested in working, and then cherry-picked to the release branch. Staging can be deployed from the new tag, and the issue verified in the higher environment before being pushed to production. This reduces the chance of creating a regression in a release downstream, thus avoiding an awkward conversation with the customer explaining why the same bug appeared twice in production.

Credit: Paul Hammant, www.trunkbaseddevelopment.com (4)

Credit: Paul Hammant, www.trunkbaseddevelopment.com (4)

With just a few tweaks, this team implements TBD. They now have a steady stream of commits to a single branch, continuous integration to enforce the integrity of the codebase, and a reliable release process that allows for patches between planned releases.

The Importance of Continuous Integration

The last example presented a team that had continuous integration built into the process of committing to the trunk. CI is not a prerequisite for TBD. However, it’s a very powerful tool for enforcing the policy of “Don’t break the build.” It’s much harder for a teammate to take down the stability of the codebase by accidentally pushing changes to trunk without running the build and test scripts when it’s a requirement for the build to pass before pushing the changes. Continuous Integration enables autonomy within the team that promotes confidence within the team. trunk-based development is a level up in software engineering and requires quality to be a first-class citizen. Every contributor is responsible for maintaining the quality of the product, and CI should include a series of gates that ensure at least the minimum standards are met with every commit. In some cases, this may simply be the application compiles successfully and unit tests pass. As the team progresses, additional testing standards can be applied. There are many automated code-scanning tools to check for common patterns leading to bugs or security vulnerabilities that can be integrated into the build process.

The most important factor in continuous integration is consistency. The scripts that are run on the continuous integration server should be identical to the scripts running on a contributor’s machine. CI should be as fast as possible to encourage running CI early and often, to ensure they comply with the golden rule: “Don’t break the build”. Breaking the build on the trunk means other engineers pulling code ends up in a broken state. We had a rule on my first software team which was not running trunk-based development, where if you broke the build you bought doughnuts for the team. “The doughnut rule”. Everyone is in for a bad time if code is introduced to the mainline without being adequately verified. Although it’s nice, it’s not a requirement for your CI to run before committing code to the trunk. On teams who are committing straight to trunk, CI can be as simple as a team agreement to run tests before pushing, CI can run on the build server after the commit lands on the trunk. Or, maybe you have some forgetful or over-eager teammates. Consider using a git pre-push hook to “force” engineers to run tests before git performs the actual push to the remote branch.

I’ve found an effective way to reinforce the culture of keeping a clean build through ChatOps. If your team is using Microsoft Teams or Slack and you have a channel you regularly communicate in, having CI post the results of the latest run, the commit, and the author gives visibility to the build. It’s a really fast way for news to travel should something go wrong. I don’t endorse chat-shaming your teammates over a build failure. But it does build a culture around quality and helps hold everyone accountable. And kudos to those teams who can keep the channel in the green all the time!

Your CI is only as valuable as your test suite. A simple CI build will catch whether or not the app failed to compile because of a rogue semicolon, but the tests should bring real value. Has the code being introduced changed existing functionality? Does the suite still have a sufficient level of coverage given the new code paths that were added? There is often a negative stigma around testing. Many teams add tests after the feature is complete, which makes testing the thing that stands in the way of getting the feature into production, or at least to the next phase of verification. Putting it in a different light, automated testing is the gateway to adding speed without sacrificing stability. Accelerate indicates that a reliable test suite makes teams both confident their software is releasable as well as confident that a test failure indicates a real defect (5).

In terms of trunk-based Development, releasability is one of the golden rules. High-performing teams take pride in testing the code they write to sustain confidence in the codebase as a whole. And pragmatism should always be the driving inspiration behind how much testing is required to maintain quality code. When you’re up against deadlines, it’s easy to take shortcuts and make concessions when it comes to testing. I have a really good relationship with test-driven development, and it can help with these issues. But when you need to slam a bugfix in for the good of the product, there is usually time to take a breath and backfill some of that coverage. At the end of the day, coverage metrics are intended to be guidelines to enforce a best practice. But as a team, you control those standards. When you take the time to improve your relationship with writing tests as a part of your development process you’ll see your productivity, confidence, and overall satisfaction rise.

Concerns with adoption

Working on a team new to high-performance delivery can introduce a regression in mindset due to fear of making a change that inevitably causes an issue. My particular experience with this issue was an ambition to be working at a faster cadence than we were. We were continuously pushing to a staging environment, and we were simply tagging the commit we wanted to release to prod and moving on. When our first serious issue came up in production while we were halfway through a sprint, we weren’t comfortable enough with the state of the application to release to prod. We broke the rule. We weren’t releasable. We spent the next two days ensuring the system was up to our standards, or the stakeholder’s standards, to fix the issue in production. Two days was not acceptable. We needed a better strategy, and we need to take the state of releasability more seriously. Our team was releasing to production about every two weeks after we demo the latest work at our sprint review meeting. In trunk-based development, this isn’t fast enough to be released from the trunk. There is too much drift between the environments at that point. I spoke earlier about the branch-from-release technique. This was a hard lesson, but a good one. By creating a release branch, we were able to cherry-pick a fix to the production code and deploy it to staging for testing without introducing any risk from the latest development.

TBD goes hand-in-hand with agile frameworks like SCRUM, Kanban, and Extreme Programming. A team using waterfall to build products likely doesn’t have the release cadence that would support a healthy trunk-based environment. It’s not necessarily a requirement, but the linear nature of waterfall generally pushes releases to production out beyond four weeks, or sometimes even quarterly. Generally, waterfall projects are associated with long-running feature branches and major integrations with the main branch. These negate the benefits of TBD by introducing merge pain and the potential for breaking the build.

One of my team’s initial concerns was feeling pressured to just “go faster.” Which isn’t the point. We simply had a problem sizing work appropriately. We were new to SCRUM and new to TBD. Our work was simply too complex, and we hadn’t found a way to drill down to the “smallest deliverable increment”. Larger stories simply carry more risk and take more time. TBD can’t get you to the finish line any faster if you’re not leveraging the tools it provides. Our mindset had not adapted to the new workflow. One experiment we ran early on was to try to create user stories that would take no longer than a day or two to get into our test environment. By doing this, we started to find the natural vertical slices that we could collaborate on with the rest of the team.

The biggest concerns my team had when introducing trunk-based development was code review. At this point, we took pull requests very seriously. Every line was meticulously reviewed before it was introduced to the main branch. Sometimes it would take days to get a PR merged. It’s not uncommon to have one or more teammates that don’t quite trust someone’s code. Removing the barrier to merging into trunk may as well have been opening the gates of hell! Complete chaos was sure to follow. It was a hard sell, but we implemented some safeguards to ease the concerns. First was the CI process. We required a pre-push hook to run all the unit and integration tests successfully before the commit was pushed to the trunk. We also really wanted to keep code review as a part of our “definition of done”. Code review is often referred to in the negative because it’s raw constructive criticism. Someone who may have no idea what your code does can offer insights into ways it can be improved. Or, even suggest changes that could prevent issues immediately, or down the road. However, when you spend a week building something you think is awesome and your colleague rips it to shreds, it’s expected to be upset that you are not in fact “done” yet. In a traditional pull-request environment, it may mean one or more rounds of changes before you can even get something tested. That slows down progress and can hurt the team’s overall performance. Consider if you could have the best of both worlds. There is a concept of “Continuous code review” that allows teams to review each other’s code without ever creating a pull request.

Continuous Code Review

Pair programming is the first form of “Continuous Code Review.” If the code review guidelines state that you must have another set of eyes look at your code, then it’s most reasonable to assume that working in tandem should keep everyone honest in following the team’s standards. Pairing is easier for some engineers than others. I enjoy spending some of my time in a pair working towards a common goal, while other times I prefer to work on my own. For instance, when working on a difficult problem that more than one person is aware of may be easier to maximize brainpower by teaming up. Or, if one engineer is writing tests in sync with the developer writing the implementation of the interface. There is also the driver and passenger approach for more experienced engineers to teach a new skill to a colleague. Each of these scenarios offers increased performance, as well as an honest code review from a teammate close to the implementation.

The adoption of pairing varies from team to team. Depending on the dynamic, a team may be made of engineers who prefer to work alone. Working alone has its benefits as well. There is comfort in being free to make mistakes, experiment with methods that aren’t pretty, or go on a major refactoring mission. Remote work can make being in a zoom or teams meeting while screen sharing exhausting. It’s not uncommon for teams to prefer to mix up pairing and soloing. If code review is important to the team and pull requests are too much of a bottleneck, how can you enforce the standards? The answer is post-commit review.

Post-commit review allows teams to commit to the trunk and group together commits, either automatically or through manual selection, to produce a diff for teammates to review. There are two tools that I have firsthand experience with:

Both Upsource and Crucible offer similar features, including reviews that can be initiated by the author or authors by selecting commits on the trunk and requesting a code review from their teammates. The experience is very similar to a pull request in Azure Devops, Github, and Bitbucket. Reviewers can leave comments, have discussions and approve or reject a review. In addition, they can track new commits being added to the trunk by a standard pattern, such as an issue tracking number. If comments have been added to an area that is updated, the comment will resolve itself and the reviewer is notified of the change. This functionality should sound familiar if you use pull requests for code review. The difference is these commits have been applied to the trunk, and the code can start generating feedback from either internal testers or real users, depending on the team’s release cadence. This allows the team to get feedback on the code, and how it operates in a real environment simultaneously.

This approach is uncommon, but it is an option. I will add the disclaimer, both Upsource and Crucible have a UI that leaves something to be desired. It doesn’t match the user experience of reviewing a pull request on any platform. If I had to pick, and I did at one point, Upsource is the better platform. Another disclaimer, as an SRE, it is a serious resource hog. For teams who struggle to get pull requests reviewed promptly, uncoupling code review and shipping code can be a liberating change. Consider the first example, “Jack”. Jack found a bottleneck with his team while trying to get feedback from the engineers, quality assurance, and design. Had he been able to deliver code to all parties at the same time, he could have gotten feedback while he was still in the development process.

Trunk-based development is more of a mindset shift than anything. Adopting TBD requires engineers to rethink how they build. It requires them to start asking questions such as:

- What is the first deliverable increment of this feature?

- How can this be deployed to production without interrupting the existing functionality?

- What effect will this have on the application if it’s deployed to production?

The new mindset begins to separate the concepts of “deploy” and “release”. Many people consider these to be synonymous. But when releases and deployments are separated, the step towards TBD and continuous delivery becomes an achievable reality.

Feature Flags and Branching by Abstraction

To calm the nerves out there, let’s tackle the subject of stability. When introducing code to the trunk at a higher rate and being ready to release at any time, teams have to account for developing new features that are not ready for customer use. Alternatively, teams releasing at lower cadences still need to be able to test new features that will take multiple release cycles to complete before they are ready to be introduced to the customers. This may be a new set of endpoints to REST API, a call-to-action on the screen, or refactoring existing functionality. There has to be a simple mechanism to protect the users from potentially breaking changes to the application in production.

Feature flags are a way to control the flow of code to gate off logic or components that aren’t ready for production traffic. They’re also commonly referred to as feature toggles. Feature flags come in many forms. They can be as simple as a build flag that is baked into the configuration of the application, to runtime switchable data that can run A/B tests and slowly introduce traffic to the new code. In any case, the flag is a simple mechanism that directs a request through one path or another.

A word of caution: By implementing feature flags, there is inevitable bloat in the code. Without properly managing the life of the flags, the codebase can grow exponentially in complexity. It’s important to handle flags like technical debt. Generally, as soon as a flag is enabled in production it can be planned for removal.

A simple example of using feature flags is to show or hide something new in the UI. We’ll use javascript and an environment variable as the simplest example.

We’ll add a new environment variable for production. Hint: This could be a commit to trunk.

// .env

REACT_FEATURE_USE_FANCY_FORM=falseThen, optionally show the fancy form. In a development environment, you could temporarily enable the form by running REACT_FEATURE_USE_FANCY_FORM=true npm run start.

const FormPage: React.FC = () => {

const useFancyForm = process.env.REACT_FEATURE_USE_FANCY_FORM;

const formProps: FormProps = {

// omitted for brevity

}

return (

<main className={styles.main}>

<h1 className={styles.title}>Fill this out!</h1>

{useFancyForm ? (

<NewHotness props={formProps} />

) : (

<OldAndBusted props={formProps} />

)}

</main>

)

}Using an environment variable is just an example strategy. In controlled cases, a constant that can be changed by the developer working on the feature would suffice. However, using a framework for handling this logic would allow for dynamic flags and more complex evaluations. Depending on the application and technology stack, baking the feature flags into a static configuration would easily allow for different flags to be enabled in a developer’s workstation versus the production or other live environment. Pete Hodgson wrote on Martin Fowler’s blog, “feature flags tend to multiply rapidly, particularly when first introduced.” 6 As I mentioned earlier, they can create tech debt if you don’t manage them appropriately. Having a dynamic feature toggle service can help alleviate some of these pains by increasing the visibility of what feature flags have been created, their age, and their status.

Feature flags tend to multiply rapidly, particularly when first introduced.

When you start paying for feature flags, you get slick libraries and tools that come with them. Most notably, you introduce the ability to “instantly” rollback a problematic feature flag. In a production environment, you should be getting the feedback on a bad configuration quickly. Being able to re-route that traffic in under 5 minutes gives developers and operators a lot of power. A few products to consider if you’re excited about feature flags and want to start investigating. First, both AWS and Azure offer configuration services that have feature flagging built in. Azure App Configuration and AWS AppConfig naturally have similar names and similar features. Both services offer flags, and a UI through the console or portal, and rollout plans to incrementally increase traffic gradually over time. Depending on where you’re hosting your infrastructure, these can make lightweight, inexpensive, and powerful tools.

If you have the budget, Launch Darkly and Split.io may be worth looking into. They go beyond feature flags and A/B testing and expand into analytics, observability, and premium developer tooling. When rolling feature flags out to a team, remember to start small and slowly introduce complexity. Feature flagging is a powerful tool, but they don’t need to be complicated to be effective.

The first example of feature flagging showed how a simple boolean environment variable can be used to safely develop new functionality. Consider a REST API that is undergoing a significant refactor to one of it’s endpoints. A simple query string parameter enabling the new logic would allow developers to work with the production endpoint, and potentially allow consumers to test it with their client applications. If the tests succeed, and all traffic is to use the new logic, the query string and any bitwise operators can be removed.

HTTP GET /api/v1/my/books?q=accelerate

HTTP GET /api/v1/my/books?q=accelerate&useAlgoliaSearch=true

If the refactoring is more complex and the control flow could be error-prone or difficult to follow, consider a v2 route parameter that could introduce potentially breaking changes to an existing endpoint, while safely maintaining the original endpoint. In this example, a consumer could be made aware of the v2 API and the functional changes it offers, while being allowed to safely fall back to the previous version.

HTTP POST /api/v1/my/books

HTTP POST /api/v2/my/books

There are plenty of ways to get creative with developing new features while protecting the build and releasability of software products. Feature flags, api versioning, dependency injection and branching by abstraction are just tools in the toolbox for a team determined to reduce their lead time. Before you decide you can’t do trunk-based development because you can’t use feature flags, consider the problem from another angle.

Continuous Delivery

Before concluding, let’s consider the practice of Continuous Delivery and how it ties into trunk-based development. TBD and CD are not the same. As demonstrated in earlier examples, it’s acceptable to have a separation between commits and releases while still maintaining a high cadence. From a fundamental level, continuous delivery is an automatic push to production that could potentially occur on every commit. The purpose of this practice is based on the LEAN movement encouraging teams to deliver smaller batches, build quality in, and automate repetitive tasks. By doing this, teams avoid the “firehose” into production where a large batch of changes is introduced all at once.

Continuous delivery’s purpose at its core is to decouple us from release planning and force us to think about how to deliver software safely, quickly, and sustainably. This is where TBD and Continuous Delivery converge. It’s more of a mindset change. If we remove the release windows, planned releases, and change review committee, how can we have confidence in the software we’re building? First, we need to ensure the software meets quality standards. From Accelerate, “we invest in building a culture supported by tools and people where we can detect any issues quickly; so that they can be fixed straight away when they are cheap to detect and resolve”[7]. By delivering smaller batches to production and running a suite of reliable automated tests on frequent releases, issues are more easily identified. In an extreme example, finding a bug in a batch of 100 commits is harder than finding a bug in one or two commits. If the issue is quickly identified, it can just as quickly be rolled back and confidently released to production.

CD is another tool in the toolbox for software teams to elevate their performance. However, it’s not a requirement or a barrier to TBD. They can be paired, adapted, or completely independent of each other.

Conclusion

A former colleague first described trunk-based development to me as “the next level of software engineering.” I didn’t require a whole lot of additional convincing, that sounded great to me! I wanted to get to that level. But he encouraged me to read Accelerate, which drives the point home. It helped me encourage a team with mixed opinions on the subject to experiment with the concepts that had the potential to improve our efficiency and our culture. We spent several sprints iterating on the experiment, investing in more quality automation to build our confidence. Finally, we reached a point where we renamed the main branch trunk and dedicated ourselves to the practice.

Some teams have already started down the path of TBD, and some may just be learning about it. Continuous improvement is not about making large radical changes requiring immediate adoption. Small changes are easier to digest and allow you to find what works best for you and your teams now while allowing for further improvement in the future.

References

- 1: “Introduction” www.trunkbaseddevelopment.com Accessed 09/12/2022

- 2 Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Trunk-Based Development. In Accelerate: The science behind devops: Building and scaling high performing technology organizations (pp. 55–56). essay, IT Revolution.

- 3: “You’re doing it wrong” https://trunkbaseddevelopment.com/youre-doing-it-wrong/#keeping-a-single-release-branch Accessed 09/13/2022

- 4: Hammant, Paul “Branch for release” https://trunkbaseddevelopment.com/branch-for-release/ Accessed 09/13/2022

- 5 Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Test Automation. In Accelerate: The science behind devops: Building and scaling high performing technology organizations (pp. 53-54). essay, IT Revolution.

- 6 Hodgson, Pete. “Feature Toggles (Aka Feature Flags).” Martinfowler.com, https://martinfowler.com/articles/feature-toggles.html.

- 7 Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Trunk-Based Development. In Accelerate: The science behind devops: Building and scaling high performing technology organizations (pp. 42-43). essay, IT Revolution.